With the introduction of the American Families Plan, President Biden added $1.8 trillion of programs to his bold legislative agenda and brought many taxpayers one step closer to higher tax rates. With changes on the horizon, many donors and charities are wondering how the proposed tax changes will impact charitable giving.

While taxes are likely to increase, it’s not yet clear precisely how much they will rise or when the new rates will take effect. The latest proposal includes several provisions of keen interest to investors. The most jarring is the 82% increase in the federal tax rate on dividends and long-term capital gains for households earning more than $1 million. Adding the 3.8% net investment income tax, this would take the highest federal rate from 23.8% to 40.8% for the rest of 2021 and to 43.4% starting in 2022, and state taxes could bring the top rate as high as 56.2%. Other proposed changes include raising the top federal income tax rate to 39.6%, limiting 1031 real estate exchanges to gains of only $500,000, and ending the step-up in cost basis, and triggering deemed realization at death for gains exceeding $1 million per person.1

President Biden’s proposed budget, released on May 29, assumes the increase in the capital gains tax rate would be retroactive to April 28, 2021 , while most other changes would be effective on January 1, 2022. Retroactive tax law change is not unprecedented. When President Clinton signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 on August 10 of that year, tax rates increased retroactively for all of 1993. Even so, presidential budgets are just blueprints. Their provisions are often changed before being passed into legislation, and Congress must still approve any tax rate changes and their effective dates.

Proposed Changes Could Spur Greater Charitable Giving

One provision notably missing from the president’s plan is his campaign proposal to limit the benefit of itemized deductions to 28%—which would have capped the federal tax rate that could be offset by charitable contributions at 28%, even for taxpayers subject to much higher marginal tax rates. This omission is a favorable surprise to both donors and the philanthropic community.

From a tax perspective, these proposed changes make charitable giving even more attractive. When tax rates increase, the out-of-pocket cost of making a charitable gift declines. And the step-up in cost basis at death has long provided investors with the ability to hold appreciated assets and eventually avoid the gain. If a deemed recognition of gains at death passes, investors should be more motivated to donate highly appreciated assets to charity during their lifetime.

Historically, charitable giving has been closely linked to growth in the economy and personal income, but donor behavior has also been influenced by changes in the tax law. Most recently, in 2018, after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the top federal income tax rate from 39.6% to 37% and nearly doubled the standard deduction, charitable giving by individuals dropped by 1.1%.2 That translates to over $3 billion less for charities to put to work that year. On the other hand, in 2013, when the American Taxpayer Relief Act increased the top federal income tax rate from 35% to 39.6% and the top capital gains tax rate from 15% to 23.8%, giving by individuals rose by 4.2%.3

Studies show that when it comes to giving, the top donor concern is, “Will my dollars make an impact?” Still, taxes are an important part of the equation. Since donors may be more reluctant to give if they fear taxes will soon be taking a bigger bite of their income, it’s vital that nonprofit development officers and planned giving professionals be prepared to share with donors the enhanced benefits of giving in the most tax-efficient manner.

Cash Gifts Are an Attractive Option, but Not Optimal

In 2020, the CARES Act offered incentives for cash contributions to a public charity (not including donor-advised funds, private foundations, or supporting organizations), allowing donors to deduct up to 100% of their adjusted gross income (AGI). This was extended for year 2021, but in 2022 it will drop back down to 60% of AGI. Still, cash isn’t the most optimal gift, especially in a high-tax-rate environment.

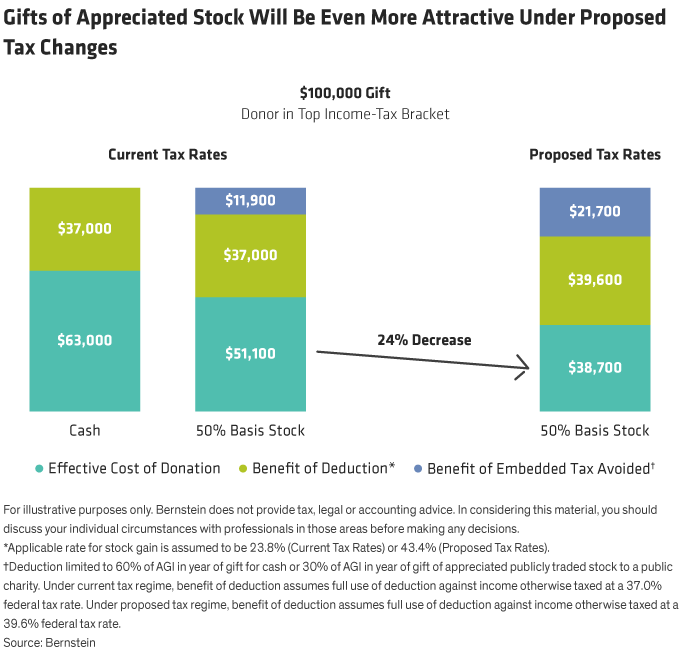

For a donor in the top federal bracket today (37%), deducting the value of a $100,000 cash gift to a qualified charity reduces the federal income tax owed by $37,000, thereby cutting the effective cost of the gift (the value of the gift minus the tax benefit) to $63,000. (Display). For those who pay state and local income tax, the effective cost may be even lower.

By contrast, gifts of appreciated publicly traded stock not only provide a charitable income tax deduction for the value of the donation, but they also allow the donor to avoid taxes on the gain in the stock. If the same taxpayer donated $100,000 in publicly traded stock bought for $50,000, the 23.8% tax on the stock’s $50,000 gain would be avoided. The extra tax savings cut the effective cost of the donation to $51,100.

If the capital gains rate for taxpayers with income over $1 million does rise to 43.4%, this benefit becomes even more attractive. After a tax rate increase, the same taxpayer could donate $100,000 of appreciated stock with an effective cost of only $38,700—a 24% reduction.

Charitable Remainder Trusts: In the Crosshairs or the Spotlight?

Depending on how the law changes, charitable remainder trusts (CRT) may be severely hindered, or they may become even more beneficial. Under the current law, the donor irrevocably contributes a highly appreciated asset (including publicly traded stocks, real estate, or private business interests) to the CRT and receives a charitable income tax deduction for a portion of the value contributed. The appreciated asset can then be sold inside the CRT without incurring any immediate capital gains tax. Instead, the donor receives an annual distribution from the CRT for the duration of the trust. Because the distribution from the CRT is taxable, the donor effectively spreads the capital gains tax over many years of distributions. Assets remaining in the CRT at the end of the trust term (typically the death of the donor and spouse) pass to charity.

Under President Biden’s proposed budget, the contribution of appreciated assets to a CRT would generate a taxable capital gain for the donor, excluding the charity’s share of that gain as determined for gift or estate tax purposes.4 If adopted, it would be a devastating blow to CRTs. However, the rules for CRTs would not change until January 1, 2022, so contributions made before that date could be very attractive.

On the other hand, Congress could decide to raise tax rates but leave the current treatment of CRTs intact. While that would increase the tax-deferral benefit of new CRTs generally, the donors who may benefit most from a CRT are those who can avoid the 43.4% capital gains tax at the time of sale, and defer the tax into future years when they are below the $1 million income threshold and subject to a lower 23.8% tax rate. For certain taxpayers, CRTs may become very popular indeed.

Worth the Wait?

So, should donors wait until after they’re certain tax rates have risen to make their charitable gifts? Not necessarily. Waiting may generate a greater personal tax benefit, but if the charity needs your contribution to further its mission, it may make sense to make the donation today. Further, many investors are considering selling highly appreciated, overweighted stock positions, hoping that today’s lower tax rates will apply. By coupling a sale with a charitable contribution, a donor can ease their tax burden this year while helping a charity with much-needed support.

Your Bernstein Financial Advisor can walk you through the different options and recommend a course of action that’s both beneficial from a tax perspective and consistent with your values.

- Christopher Clarkson, CFA

- National Director, Planning | Foundation & Institutional Advisory

- Jennifer Ostberg, CFP®, CAP®

- Director—Personal Philanthropy Services

1 Fact Sheet: The American Families Plan, The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/28/fact-sheet-the-american-families-plan/.

2 Giving USA 2019: Americans gave $427.71 billion to charity in 2018 amid complex year for charitable giving. https://givingusa.org.

3 Giving USA: Americans Gave $335.17 Billion to Charity in 2013; Total Approaches Pre-Recession Peak. Lilly School of Philanthropy, June 17, 2014, https://philanthropy.iupui.edu/news-events/news-item/giving-usa:-americans-gave-$335.17-billion-to-charity-in-2013;-total-approaches-pre-recession-peak.html?id=127.

4 General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals. Department of the Treasury, May 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2022.pdf.