Blindsided. That’s how some investors feel about the pandemic’s impact on their investments. But for those who navigated the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) more than a decade ago, hard-earned lessons on diversification likely soothed some of March’s equity market sting. Coming out of the GFC and over the subsequent 11-year market expansion, those investors readily adopted private investments in their portfolios. Stories of robust returns enticed others to take the plunge as well.

In recent years, expensive public stock valuations attracted more investors as real estate, private equity, private debt, and specialty funds grew comparatively cheaper. Enraptured investors found that private investments delivered equity-like performance with a differentiated stream of returns that resulted in lower volatility. But the end of the longest public market bull market in history is forcing private investors—many of whom are new to the asset class—to confront an unknown beast. A market downturn. Will the principles of private market diversification hold? The answer lies in the investment cycle.

Characteristics of a Cycle

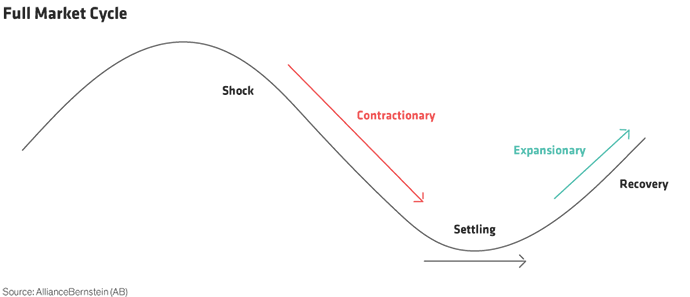

Complete movement through a period of expansion and contraction, and the steady state in-between, defines a full market cycle. We characterize these phases as shock, settling, and recovery (Display). Each has distinctive traits that differ between public and private markets for one reason—illiquidity.

Illiquidity Can Stave Off Natural Inclinations

In public equity markets, where investors can buy or sell at any point in time, fear—of losing money or missing out—often dictates buy/sell behavior. This psychological underpinning tends to lock in losses when markets fall while pushing momentum trades when markets soar—exacerbating both upside and downside moves.

But in private markets, which are typically illiquid and often have a multiyear lock-up period for invested capital, investment results are less influenced by market gyrations. That’s a singular advantage: Shielding managers from the pressures of short-term market sentiment affords companies time to develop and execute a long-term plan. And since managers prefer to take control positions in companies (unlike owners of public equity), they can effectuate real change. The long-time horizon and control position mean illiquid investments should be evaluated over a full market cycle, not just here and now.

Inner Workings of the Cycle

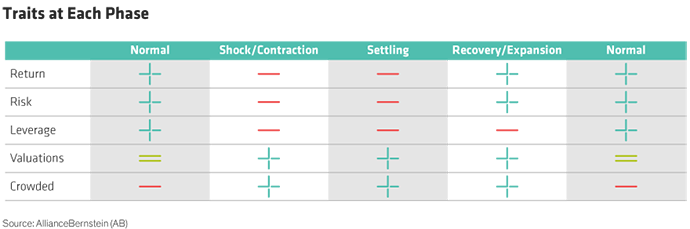

In a normal market, returns on investments, amplified by leverage, tend to rise while risk remains low. Valuations appear appropriate, but trades begin to crowd as new investment dollars chase similarly robust returns. It’s hard to find undervalued opportunities, and at times congested trades can push prices irrationally high. That’s good when you’re a seller, but not when you’re a buyer.

2019 was a signature normal market: Robust returns and crowded trades drove valuations higher and eventually led to concerns that massive amounts of accumulated dry powder would force undisciplined purchases. When COVID-19 hit, the market shifted from normal to shock—a completely new environment for many private investors. How will private markets fare in this phase, and through settling and recovery? (Display).

Shock and Settling: While these phases look similar, they differ in magnitude. After a shock in the real economy, returns fall as risks—including leverage—rise. Valuations become attractive, and competition lessens.

At this time, prizing liquidity forces many investors to hunker down and shy away from making new investments. Private investors can take advantage of the market weakness and put dry powder to work, often at discounted valuations. And owners in the position to effect change do so. Prudently seizing market opportunities when others are fleeing tends to generate strong returns as the cycle moves into recovery.

With that said, even absent the overhang of quarterly reporting, private market managers must mark the value of their investments to reflect the changing economic backdrop. Because they happen infrequently, and only an investment’s exit reveals the true price, marks are often aggressive to the downside to depict a conservative valuation. So, in some cases, investment values fall after a purchase. Still, as the shock phase moves into settlement, the majority recapture, then grow their worth during recovery.

The years following the financial crisis—2009–2010—were typical of these phases. The strong returns during those years came from private market managers leaning into the market when other investors were pulling out, buying high-quality assets at fire-sale prices, and managing their businesses appropriately. Some valuations initially fell but came back and grew during the subsequent recovery.

Recovery: As settling moves to recovery, returns rise, risk falls, and leverage is carefully applied once again. But attractive valuations and uncrowded trades persist as lingering fears hold investors back from dipping in. As recovery deepens, valuations become more expensive and trades more crowded—heralding a normal market—and the cycle begins anew.

Shock Often Leads to Returns’ ‘Awe’

Private markets must weather the initial shock of a recession and any associated markdowns that funds need to take. At times, the shock can overwhelm investors, but commitment and patience generally pay off as recovery takes hold. Plus, investors who are willing to allocate new capital to illiquid markets at a time when others remain fearful usually receive ample compensation for the risk. In the end, awe-inspiring returns born of an initial shock are often worth the wait.

- Alexander Chaloff

- Chief Investment Officer & Head of Investment & Wealth Strategies