This is the third installment in our “What If” series. The first, What If [Insert Name] Wins the Election?, looked at how elections influence market returns and the second, What If the Markets Party Like It’s the 1990s? considered the possibility of a longer economic expansion. As a reminder, these blogs are not usually our base case, but we consider a range of possible situations that could play out, address the “what ifs” we are talking about most and their impact on the markets.

Trade wars. Super viruses. Nuclear missile tests. Elections. Uprisings. These stressors are just some of the headlines hitting the 24-hour news cycle. For many, these events affect our sense of security or wellbeing. They may also impact our financial confidence. However, history tells us that geopolitical events rarely have a lasting impact on the business cycle. But what if one of the numerous geopolitical issues we’re facing today sinks the market?

Bernstein’s Co-heads of Investment Strategy, Beata Kirr and Alex Chaloff, sat down to discuss what lessons we can learn from history.

Beata: I recently read that more people are suffering from anxiety and depression today because they are constantly barraged with news—amplified by ‘always-on’ social media platforms—and most of that news feels “bad.” Alex, what do you think? Is there more headline-making news today than in the past?

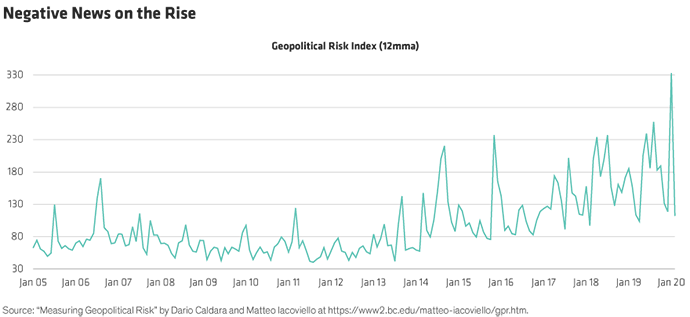

Alex: Well, yes…and no. The Federal Reserve Board* creates the Geopolitical Risk (GPR) Index that counts the occurrence of words related to geopolitical tensions in 11 leading international newspapers. The data show that geopolitical headlines globally are indeed rising, so there is definitely more source material. And, unfortunately, we live in a world where attention spans are super short, so the most outrageous, or interest-grabbing headlines win. So yes, negative news headlines are on the rise, but many of those are also hyperbole, not real events (Display 1).

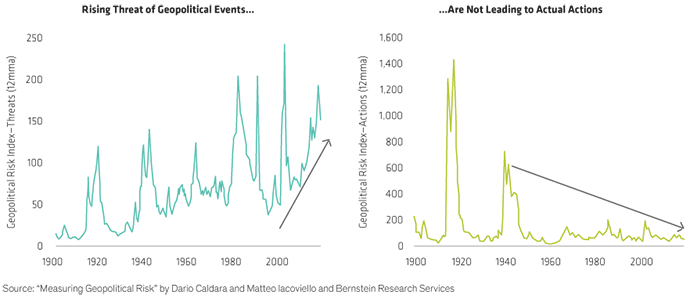

Beata: That confirms my suspicions then. But, while geopolitical headlines may be rising, these news-making events have not resulted in full-blown crises, as we saw with the various wars between the 1940s and 1960s. In other words, today’s events, according to the GPR, have been more threat—warnings of potential terrorism, nuclear tensions, or military-related strains—and less action—actual terrorist acts or the beginning of war (Display 2). The real question is: Are these headlines impacting the markets?

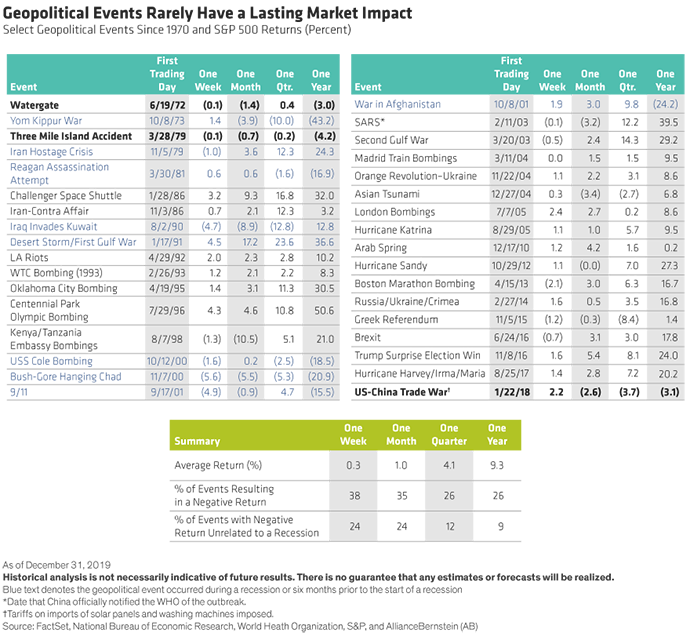

Alex: My gut reaction to this question was to just say, “yes”, but we need data. We looked at 34 geopolitical events beginning in 1970 and the subsequent short- and long-term market response (Display 3). These events were chosen to reflect diverse types of news over the period, ranging from political to weather-related.

What we found was that one month following any event, the S&P 500 Index had a negative return just over one-third of the time. But one year after any event, the market was positive nearly 75% of the time. So, both one month and one year later, the market had looked through the headlines and, the vast majority of the time, delivered a positive return.

Beata: You’re right. The average one-year return after all events was 9.3%. That’s surprising to many, but it does make sense. Most geopolitical events don’t impact the real economy in any meaningful, long-lasting way. So even if the market heeds negative news in the short term, it tends to focus on fundamentals and looks past headlines longer term. But there were some outliers to the overall trends, of course.

Alex: There always are! Of the nine events that delivered negative returns one-year post event, six occurred during or within six months of a recession. In other words, there were concurrent economic trends that caused the markets to fall, and the geopolitical event may have contributed to the decline, but it was not the sole reason for it.

Beata: But there are three events—Watergate, the Three Mile Island accident, and the US-China trade war—where the markets were down, and there was not a corresponding recession. What made those different?

Alex: The 1970s were not great from an economic standpoint. Double-digit unemployment, stagflation, rising oil prices, and political turmoil hit all at once. While there wasn’t a recession at the time of Watergate, all signs pointed to being on the precipice of one. A year and a half later, a 16-month recession hit full-force. So, while having the US President embroiled in scandal and resigning is never a good thing, it appears the economic pressures that had been building during that time period were the primary reason for the market’s decline.

Beata: That makes sense. We also observe that the Three Mile Island accident, a nuclear reactor meltdown that many of us remember well, occurred roughly nine months prior to two successive recessions. Both the 1980 and 1981 recessions were triggered by tight monetary policy, which was put in place to fight mounting inflation, which reached 11 percent in June 1979. At the same time, unemployment went from 7.4% to 10% and long-run interest rates increased from about 11% in October 1980 to more than 15% a year later. In fact, prior to the Global Financial Crisis, the 1981–1982 recession was the worst downturn since the Depression. So while the accident called into question the safety of nuclear energy, it was the economic impacts of high inflation coupled with growing unemployment that had a bigger impact on equity market returns.

Alex: And that brings us to the US-China trade war. The event itself, unlike the last two events, financially affected US and global companies, so it’s easy to see how this event could impact market returns. But trade was only part of the equation. Stocks fell amid fears of slowing economic growth, in which trade was a factor, and concern that the Fed’s monetary policy was wrong. Despite these worries, investors eventually shook off the dispute—the US market rose 10.4% between the start of the dispute and the signing of the initial agreement, roughly two years later. Although this event highlights that geopolitical events could weigh on markets longer term, the reason it lasted was because it had a real financial impact on the economy.

Beata: And today we’d be remiss if we didn’t talk about the coronavirus. Just the other day the market fell 1000 points on fears of a pandemic. But we believe, like other health-related events in history—SARS, for instance—market impact will be short-lived. Markets hate uncertainty, and a spreading virus emanating from a country as economically significant as China is highly uncertain. Given China’s role as a key player in global supply chains—supply chains that are now being disrupted—the markets’ reaction is understandable. As well, demand is likely to fall meaningfully in the near-term. But the Fed has taken an early step toward trying to soften the blow. While monetary policy accommodation is not a panacea, it can easy financial conditions – buying time for the damage to begin to recede.

Alex: I agree. So Beata, where does all of this leave us?

Beata: We expect that geopolitics will continue to garner headlines and may cause short-term market blips as news is digested. But as has been the case in recent history, we don’t foresee geopolitical events swaying long-term market returns, without the presence of underlying economic factors. With that said, it’s not out of the realm of possibility that several incidences converging on the market at once could drag it lower as sentiment collapses and pulls down valuations. That’s why we assess the probability of these types of events in isolation, and together—to understand the possible consequences, and stress-test various scenarios on our portfolios. We consider the What Ifs so that you don’t have to.

* https://www.policyuncertainty.com/gpr.html

- Alexander Chaloff

- Chief Investment Officer & Head of Investment & Wealth Strategies

- Beata Kirr

- Co-Head—Investment & Wealth Strategies